Driving back into town we were again confronted by dead traffic lights.

Emily’s little sister Becca had moved into our upstairs. She’d purchased her first house not long before Helene hit, a bit in the sticks in West Asheville, and had taken the opportunity to use our place as home base to be closer to her sister’s family. We’d given our other key to the Scroggses so they could keep using our stove.

We installed Rudy and refamiliarized ourselves with the 17th century. The house had that stale quality that comes with sustained powerlessness. It’s one thing to be in a home freshly unplugged from its necessary systems, it’s quite another to return to one. The gloss of adventure had chipped off. It reminded me of camping for a day too many.

Headed east to Daymoon we were immured in a seemingly impromptu and, I thought, unusually smelly traffic jam. At one point a WastePro truck, turning out of the Fairview Ingles (F’Ingles) parking lot, received the traffic jam’s applause and celebratory honking. Turned out the parking lot had been converted into an emergency trash drop-off.

Daymoon had a bit of an undressed quality: doors thrown open, box of gnarled giveaway organic produce on the back porch, silent inside but for motley unbathed guests thumbing their phones or entertaining their children. Several of the patio tables were occupied. My barista, Raine, had taped handmade signs to the doors specifying hours and listing our paltry offerings: cold brew, chai with dairy-alternative milks, nothing iced or hot, bottles of water and OJ, cash only, pay-what-and-if-you-can. Many of our outlets were being used, some for essential medical devices. On the counter by the register were pages of community information: places you could get a hot meal or take a shower, places with wi-fi. Know something? Grab a Sharpie, make an addition.

It became a feature of our lives that we would have brief encounters with strangers concluding in public jags of gratitude crying.

We unloaded the rest of our CostCo take, most of which went in a free pile that would gradually migrate to the covered front porch. Someone asked for help at the business next door, a charity gift shop called Signs for Hope: a Virginia church had sent a pallet of bottled-water bricks in a U-Haul trailer. We were well-equipped for the task: I brought a cart from Daymoon and joined the train of ants. Ultimately our landlord would plant a sign between our two businesses with arrows pointing at each and the Sharpie-scrawled caption: Take what you need.

Afterwards I sat for a minute outside considering the scene before driving home, packing my electric lawnmower into the trunk and coming back to cut the grass. My employees said they’d never seen me put off such dad vibes.

The next day was a Friday and I worked. It was my first time behind the counter in months. A steady stream of people came in. Shellshocked, wet-eyed, grizzled, tentative. We’d done special shopping for some friends of ours (kitty litter, generator oil) who swung by to pick up. A regular came in with her partner, a temporarily unemployed tattoo artist and former barista who’d made a coffee trailer out of a 1969 Serro Scotty camper. His name was Dakota. He inquired as to whether or not I’d be interested in possibly making use of his camper. We exchanged numbers.

Right after locking up I noticed one of my most solid long-time regulars shuffling crestfallen back to his car. “Mr David, come in!” I said, opening the door. “Let me get you something!”

Mr David was one of the first customers whose names I learned upon taking ownership of what was then, in 2017, called Mountain Mojo. A financial advisor straight out of Lake Woebegone, Mr David was not to be seen outside of a vest and tie. He was an ironed, buttoned-down, mild- and scrupulously-mannered fellow, aspects of whose personal life had become known to us in the shop—as will happen at heavily-trafficked establishments with low turnover rates. We knew before the storm ever hit that it hadn’t been the easiest year on record for Mr David. That day he resembled the Man from Snowy River a couple decades after they’d stopped filming. “Are you open, Devin, really?” he said, unshaven and wild-haired, operating within a sour tang of the outdoors, his rectitude bent but not broken.

He told me he’d only just that day made it out of his house. This was the situation with many of our regulars. Much of the appeal of Fairview is its mountainous terrain. People above a certain age built or bought their houses decades ago, before the market had tilted dramatically up. They have steep driveways and many-leveled stick-builts burrowed into the sides of mountains replete with old-growth trees. They have wells and generators as a matter of course—and hopefully their own chainsaws. Mr David had been stuck at his place five days.

It’s amazing how tenuous the social tethers are that keep us in place. While Mr David opened up to me from the cave of his forced isolation, I could hear Hobbes chuckling in the background. With a hushed voice and wide, excited eyes, he told me how he’d learned to confidently “take care of business” out in the open in spite of the proximity of neighbors. I’m fairly certain his relaying this bit of news was the result of a miscommunication, but miscommunications are easy when one hasn’t been communicating at all.

A fairly universal takeaway from the disaster was the resolve to become better preppers.

That night we ended up drinking beers at the Alex’s house around a fire with some of their society. I couldn’t stop talking about the Great Condiment Reset, kept polling everyone as to whether or not they’d adopt stringent new protocols when it came to restocking.

Some of the funniest/awfulest reading of my Helene-time was a Reddit page of tips from Katrina-survivors. When somebody brought up refrigerators the subject overwhelmed the thread for pages of scrolling. The upshot was: Whatever you do, don’t open it. If there was any food in it at all, and power was lost, and everything came to room temp, never open that. Wrap it like you’d wrap a mummy in duct tape, take the thing to the sidewalk, put warning signs all over it, buy a new fridge. The topic recrudesced the odor, tickled awake people’s PTSD. A man whose grandfather had purchased seven pounds of fresh shrimp just before Katrina. A man whose heart went out to the kids he saw stealing his fridge from the sidewalk.

Hence the purge prior to our leaving for Matthews and why I now thought we’d finally be able to exercise some adult control over the condiment rebirth.

That frivolous discussion was folded in amongst general ideas for better future prepping. We were all going to be better stockers of water and batteries and camping showers and fuel and canned goods.

Every day was a blur of schlepping water. We’d returned from our pillaging of CostCo with five-gallon buckets (and extra lids to give away). Lids and buckets with lids were the cigarettes of our prison economy, where every day was consumed by preparations for a sacred daily dropping of a carefully shepherded deuce.

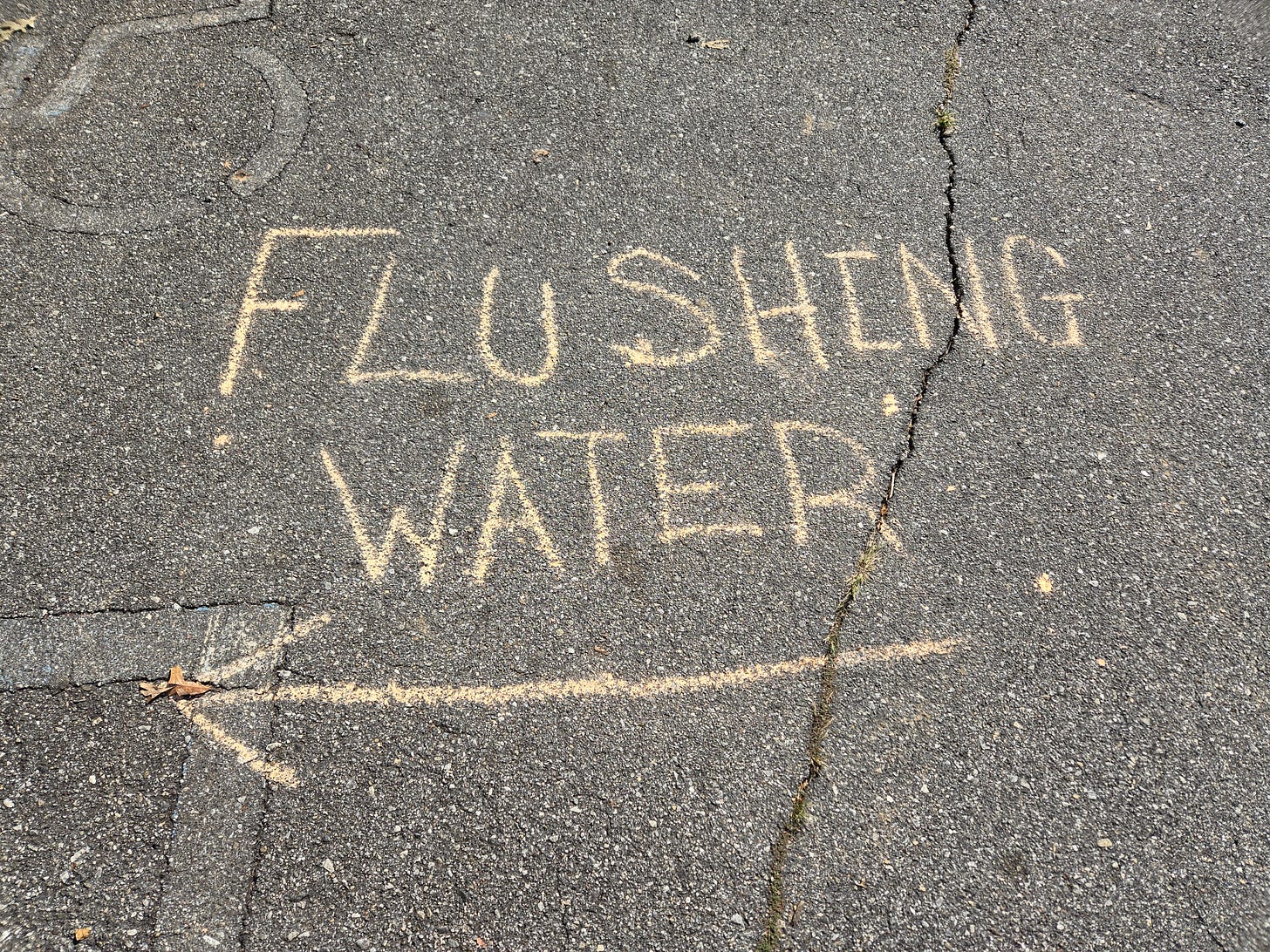

Landis told us that a local engineer had figured out how to distribute his swimming pool to the masses. He could be found at the church down the way daily from noon to 3 “while supplies last.” Becca made regular trips with first 4 and then 6 and then 8 5-gallon buckets to the house of a sister in Waynesville who had water. Our upstairs bathtub was getting low. The one downstairs had leaves in it from recharging. By this time you could fill up with potable water at World Central Kitchen stations around town. You had to make sure to keep straight what was for drinking and what for flushing.

On Saturday morning I woke up to a call from Dakota: he’d brought his camper to the shop and was ready to get things set up. We spent the better part of the morning towing into place and being introduced to Pearl. At one point Landis texted to ask if we had power at our house.

When we got home a lot of our friends had come over to the Scroggs’s for a final cleaning-out and saying-goodbye party. We parked and walked directly over to say hi and hangout, and so it was from their front stoop that I observed our porch fan working for the first time since the storm.

With electricity our internet surged back to life. Within five minutes of realizing we were on the grid again I had a playoff baseball game on tv. “This is a day of miracles,” I told friend Justin. “This is a day of miracles,” I told his wife, friend Anna. “This is a day of miracles,” I told Cara and Cliff and their daughters Adelaide and Willa. The weather was immaculate. A gaggle of us spread out on the warmth of our back porch and talked lazily in the sun. I knew better than to broadcast my unsullied joy to these tired parents, but I couldn’t help myself.

Naturally, the fates had already laid in my comeuppance.

The next day, Sunday, October 6th, Daymoon stalwart Nicole and I opened the camper with a limited menu. The machines were socked in to 5-gallon jugs of potable water. We plugged the entire camper into an outlet in the shop.

It was too short for me, super close confines for two, and initial progress was slow, with cascading power outages resulting from too many boilers heating simultaneously on too few circuits, but at the end of the day we’d found a groove.

Meanwhile my staff at the new shop were more than making do while earning massive kudos from the community. With two shops sort of going and the continuing maze of federal aid and now local grants to negotiate, I was busy. A.’s work had been derailed so she’d determined to start volunteering. Things were looking up.

That Sunday, while taking out the trash, I thought conscientiously to myself about being careful. Be careful, Devin, I told myself. This is the time, when people are exhausted, that they make stupid mistakes and hurt themselves. I remember thinking this, mentally enunciating the words as I climbed the broad uneven steps from our front yard up to the road and the wheely-bins. I don’t typically think in complete sentences, which is why I remember it so well. I thought my thing, tossed the trash, noticed that Tim and Meagan had left a light on in their house, took a careless step down, folded my ankle, and crumpled immediately to my ass.

We’d go to Urgent Care in the morning, where they told me they didn’t think anything was broken. I got a boot and crutches out of it.

The internet kept going out and staying out for days at a time, but who were we to complain? (I complained.) I encamped on the couch with my laptop and baseball intermittently available. A. volunteered at neighborhood distribution sites. The shops assembled into a state adjacent to normal.

And one day, while we were taking showers and doing laundry at the house of an acquaintance who was on a well, Shelix texted to tell us there was water in our pipes again.

The aftermath is weird.

Most people were lucky and avoided the worst. Most even avoided the least. Were you to take a utilitarian yard stick to the event, you’d find that the smallest percentage lost everything. 43 of them in Buncombe County lost everything. A slightly larger group lost a very great deal—homes, businesses, vehicles, real property. Loved ones.

Approximately 400 commercial buildings were destroyed. More than 1,000 bridges and 6,000 miles of road were impacted. 126,000 houses took damage.

Everyone else was inconvenienced.

They were severe inconveniences, particularly for the time and place. The kind that were not, as a rule, once classified as “First World problems.” But inconveniences is what they were.

That’s a shallow analysis, first blush; an initial assessment of the bomb’s landing site, the smoking crater within its rings of debris. There’s the psychic toll to consider, the psychological, certainly the long term economic.

Governor Cooper has fixed a statewide price tag of $53 billion on Helene. A quick googling tells me this is an historic amount, that only 8 hurricanes have ever eclipsed the $50 billion threshold—most recently Sandy, Harvey and Katrina.

$50 billion is the estimated cost to rebuild Gaza. It’s the bottom line of a loan organized last June to Ukraine to abet its fight for continued sovereignty. It is how much the Center for Economic and Policy Research estimates the crisis of joblessness among black men costs their communities and the U.S. economy every year. It’s about how much we spend annually on medical costs pertaining to non-fatal falling injuries among older adults. It’s a tad less than the total net worth of Stephen Schwarzman, founder of Blackstone and, as of this writing, the 27th wealthiest person in the world1. It’s a touch more than the current value of the Dallas Cowboys, Golden State Warriors, Los Angeles Rams, New York Yankees, New York Knicks, and New England Patriots put together.

Our favorite burgeoning nearby commercial district was demolished: two craft breweries, the animal rescue, the thrift stores. Long swaths of the thriving River Arts District, perhaps Asheville’s leading tourist draw, were wiped almost completely off the map. Biltmore Village, destination location for the bougie shopper, is strewn with debris, the river running through it littered with wrecked shipping containers and automobiles decorated with emergency spray paint indicators—about which macabre notions proliferate. Ghoulish stories spread of limbs and bodies discovered in trash piles, of Lowe’s employees forced to be at work who perished there. In parts rage still simmers at area corporations who did not cover themselves in glory. It’s assumed fact that Ingles grocery stores let food rot on their shelves rather than open their doors to the needy. It’s known that the Grove Park Inn kept its swimming pool intact. A customer of mine, a former Navy SeaBee, submerged himself completely in the world of search and rescue in the immediate aftermath and was known to haunt the environs of Daymoon, marooned in his phone, desperate to secure radios and supplies, becoming unhinged at the daily reality he saw progressing apace, heedless of the lost. Stories circulated of people clinging to their flood-born houses, waving goodbye to their neighbors. A customer of mine took in an abandoned kitten she named Helene. Business is slow, but people trickle back in, people we haven’t seen in months, returning finally from the disaster fall, gingerly taking stock, picking up the pieces, seeing what they can form now.

Our home has changed.

Remember when Bill Gates was the richest man in the world in 1995 with a net worth of $12 billion?

Such good writing. Such insight.