Our brother-in-law Greg had navigated us out of Asheville the previous night with directions texted from his phone. They were supposed to allow for road closures but in fact our path just getting out of the neighborhood was blocked in multiple places. Fallen trees were still super common1 and utility crews were working nonstop. In South Asheville we were greeted with functioning traffic lights for the first time in days. At one—a green one—we waited as a long row of white municipal trucks hauling emergency rescue boats pulled out of a box store parking lot. They were from a town in Arizona.

Driving out we shared the highway with emergency vehicles from all over the country. Trucks coming in laden with 250-gallon totes of water; military supply convoys; people in Fords towing trailers tightly packed with supplies. The exodus was overhyped or we’d beaten the crowd. It was quick work easting. Eventually we even saw calmly operable gas stations.

Little Pal Rudy was perfectly silent in his carrier in the back seat, which had just enough room to contain him. For the first half of the journey, that is. The second half was accompanied more or less incessantly with his feeble, scratchy protest meows. A younger child, only with Truman’s recent passing had he ever had much of a need to speak up.

The names of the streets you pass on the way to Monica and Greg’s are Kilkenney Hill, Monaghan, Fairchelsea Way… According to longstanding tradition, it is my duty to declare these roads in an at least enthusiastic Scottish brogue. Strange decision: Would doing so this time be in bad taste? Would it be a vote for continuity? Would it be comforting, irreverent, needed levity, rude? I compromised and intoned them quietly, performing wistful, performing bittersweet.

We took showers first thing, fed Rudy, and went to sleep.

My sister- and brother-in-law’s guest suite is a cave down in their basement. When we awoke that first morning there—Monday, September 30th—we immediately started crawling around getting acquainted with our space in the dark. It didn’t occur to us for a few minutes that we could simply turn on the lights.

We’d gotten in too late the night before to see anyone and then we’d slept in too late to greet Monica or the nephews on their way out the door. Greg however was working from home, so for a few minutes he and I refamiliarized ourselves in the kitchen of their Matthews, N.C. house.

This would be our first experience of setting foot in the ongoing world. We’d left the state of emergency behind; here people still went to work and school as usual. But there was immediately the feeling that we’d brought the emergency with us—that it clung to us like a film, encased us like a bubble.

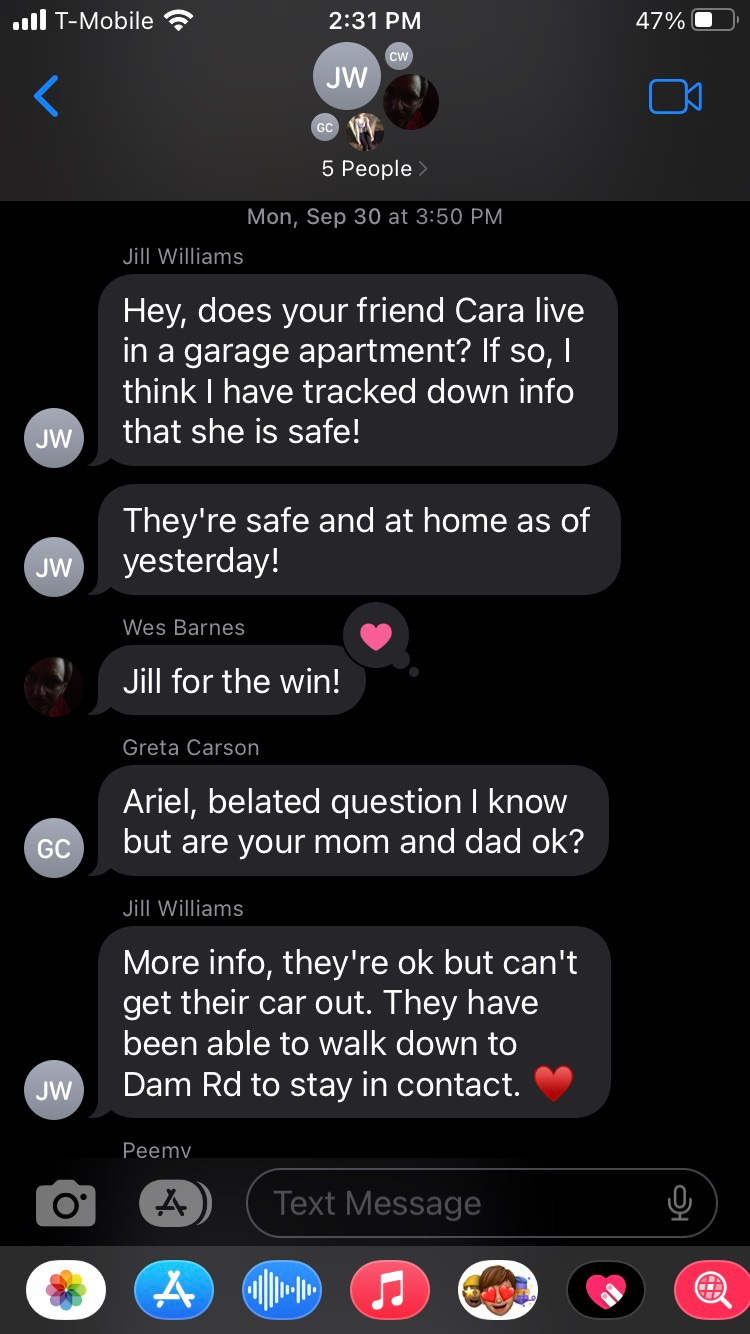

I made us coffee and went back downstairs. Rudy was hiding under the fold-out couch. A. was on the phone with Missing Persons, reporting a friend of ours. Cara and her boyfriend rented an old house on the banks of the Cane River in Yancey County. We knew Yancey had gotten it bad. Now that we were once again in the 21st century, awash in electricity and internet, we were starting to see just how bad it had been.

That day I’d spend the entire morning and afternoon on my in-law’s delightful screened-in porch, online. I got the ball rolling for unemployment for my staff and applied for SBA and FEMA assistance and filed insurance claims. I couldn’t have known it at the time, and (being an optimistic sort) wouldn’t have expected it, but from all these efforts I have, almost exactly one month later, almost nothing to show. Insurance help is negligible (a total of about $700 after my deductible is paid), the SBA doesn’t have any money until after the election, FEMA obliged us a check for $750 very quickly, which we dearly appreciated, and the unemployment ball stopped and rolled backwards for a while before dropping into a pothole somewhere, disappearing entirely, and emerging much later as a glitch-riddled dozen of smaller balls all bouncing in different, glitchy directions.

We trekked into town that first day just to walk and find something to eat. It should have been an experience of normalcy, but we weren’t able to relax into it. Seated on a patio at an exuberantly southern breakfast joint, we became People of the Phone.

Helene would become the deadliest American hurricane since Katrina. The flooding it caused in Asheville was the highest in recorded history, topping the one in 1916 by nearly three feet.

She was a late bloomer, a child of the Caribbean Sea, not—in the more traditional pattern—a child of the colder more southerly Atlantic waters. This is a thing that’s been happening recently, according to meteorologists, a weird thing they can’t explain. Hurricanes formed in the Caribbean develop faster. Not only does that mean less warning is given to communities potentially in the path of the cone, it means that the warnings that do get across are less likely to convey the true destructive force the storm will possess by the time it makes landfall. Helene, for instance, went from Tropical Storm status to Category 4 in two days. You see a man in the distance weaving clumsily in your direction, why would you ever anticipate his amplifying into a tractor-trailer going 100 in a matter of moments, blotting out your sky?

She made landfall near Perry, Florida, right in the armpit of the state, late on Thursday, September 26th. She was five and a half times as long as Hadrian’s Wall and striding north at 40 miles per hour.

By then, it had been raining in Western North Carolina for 30 hours already. Preceding Helene was a shitty forward echelon of gloom: a cold front that had come up from Atlanta and stalled over the mountains. Enjoying its stay (as we tend to hope tourists will), glutting itself on Helene’s approaching outer bands, the stalled front dumped three months’ worth of rain on the Asheville airport in a day. Ground: soaked. Rivers: rising. Table: set.

A. said: What is a hurricane if not the ocean picking up its skirts and hurrying over to pee on the ground?

As Helene rushed to squat over what local son Thomas Wolfe famously described as the teacup in the mountains2 something called orographic lift occurred. This is when hiking up into elevation causes the air in a storm to cool and condense and precipitation to increase.

By midnight on Thursday…streamflows were already running at daily record high levels in upstream, upslope parts of the French Broad River basin. The rain continued all day on Thursday as the frontal boundary had barely moved and Helene’s outer rain bands were closing in, adding even more moisture to the mix. More than nine inches fell that day across southern Yancey County. - “Rapid Reaction: Historic Flooding Follows Helene in Western NC” - Corey Davis, N.C. State Climate Office, Sept. 30th, 2024

I am not someone blessed with an intuitive grasp of facty things. I don’t seem to intellectually inhabit a grid of measurements and directions. I can never remember which is longer, a meter or a yard; I’m still pretty pissed off about a 9th grade encounter with “irrational numbers”; and, when driving home from out of town, I seem to default to a belief that I am coming from the south. All this is to prepare the ground for the confession that I was confounded by the measurement of rain in inches. I kept getting tripped up on the volume of the container. Surely the volume of the container matters, no?

The volume of the container does not matter. What matters is that the receptacle’s mouth not be substantially wider than its tank. As someone on Reddit gently explained, a football field completely covered with containers of different sizes would, after a rain, have the same height of rain in each container, which is the amount of rain that fell from the sky onto the field.

In Yancey County, where our friend Cara lives, five-day totals exceeded 31 inches. That’s more than half its annual average total unleashed over the course of a work week. Asheville Airport raked in fifteen-plus inches. In all, Helene dumped 60 million Olympic swimming pools of rain onto the southeast in a couple days. If you have a hard time visualizing 60 million Olympic swimming pools, maybe you’ve been to Niagara Falls and can conjure in your mind the ceaseless roar of its majestic foaming cataract. It takes Niagara Falls 619 uninterrupted days to fill 60 million Olympic swimming pools. The Mississippi River empties 60 million Olympic swimming pools into the Gulf of Mexico every 100 days. 60 million Olympic swimming pools is 40 trillion gallons of water. That’s how many jugs of milk I poured down the drain 1 trillion, 666 billion, 666 million, 666 thousand, 667 times.3

We’d stay in Matthews four nights.

At one point a fellow refugee found us by our bumper stickers. We stood in the Ribreaus’ screened-in porch and introduced ourselves and established mutual connections and swapped stories of the flood. Joanna too was staying with family in the same area, had fled around the same time and felt an odd gnawing to return.

It seems now an unusual desire and at the same time perfectly natural. Life, if you’re lucky, has so little drama in it. Often lately I’ve found myself ruminating on how fortunate I am to be a kind of boring dude. Which is to say: I don’t mind eventless days. It’s a privilege to be caught in the gears of the weeks if they’re soft enough and the weather’s nice, if you can at least sell yourself on an illusion of liberty. People like me, who perhaps exemplify psychologically whatever course evolution has taken in our particular node of culture and spacetime (by which I mean to imply, without using the term, because there seems something pernicious in it: people who are “well-adjusted”), can go great stretches of days without needing anything important to happen. Then, when something important does happen, it’s very exciting. Which is why I was grinning like an idiot by the floodwaters Friday morning while—I now know—actual people had died, were in the process of living their last moments on Earth, were literally dying in that moment. 232 at latest count.

A great aberration in your days, though, has its own gravitational pull. There’s no sense denying it, even if it makes for macabre or unflattering contrasts. We wanted to be back where the thing was happening, not flung out centrifugally from its center, bathed and well fed and online among the denizens of the ongoing world.

We kept waffling about what to do. Everyone was saying in Asheville that most people would have their power back by Friday evening. We wanted to be there. At the same time we put out feelers for longer-term stays elsewhere—just in case we changed our minds or things got worse back home.

I sent information-dense text messages to my staff, touching base, gleaning the internet for them.

This is pretty weird but I experienced my second ever “golden wave” night of lucid sleeping: a happening seeming to coincide with extreme exhaustion and insomnia, in which the recipient remains awake as his body falls asleep, a hypnagogic event akin to the “nightly” routine of the dolphin, who sleeps one eye and one brain hemisphere at a time. The shuddering wave that signals or accompanies the body’s descent into sleep is felt as a pulse from the feet up. It’s in an entirely separate silo from sexual pleasure but as far as physical sensations go almost unutterably delightful… My hypothesis is that it is a reward our unconscious bodies absorb for achieving sleep, perhaps an incentive we’re only subconsciously aware of.

Some resourceful friends of ours Facebook-stalked and located the friend we’d reported missing. Cara and Kent were safe but unreachable. “I love you,” Cara texted Arielle simply when she could finally get word out. We wept.

The Mets played some very exciting baseball.

Richard and Peggy made it out of Asheville. Both COVID-positive and ailing, we enjoyed a socially distanced pizza party.

Arielle decided to abandon the hair-growing project and shave it off.

And, on our very last day in Matthews, we paid a visit to basically every large retailer you can think of. My first time hitting up a CostCo. The place was practically SRO. We invented a parking space at the end of a row. Filled up two carts with canned food and potable water, cat litter, wet wipes, camping accessories…the austere tally of essentials magnified by crisis. Everywhere we looked for camping showers and gas tanks, but nobody had them. Everyone was doing the same thing we were. Finally having negotiated the impressively regimented near-pandemonium of the checkout lines, I asked the guy, “Is it always like this or is this hurricane relief?”

“No, it’s the longshoreman’s strike,” he said.

What?

He told us a longshoremen’s union had gone on strike and everyone was worried prices were going to shoot up. It occurred to me that, in the 2020s, you can, at any given time, browse from a menu of reasons to panic shop.

The next day we woke up early and drove back into town. In a neat exercise of give and take, we bought more water every time we stopped to pee.

You just finished the penultimate post of the Helene Chronicles! If you liked it, please indicate within the heart! And share liberally!

Upwards of 40% of trees in Buncombe Country were damaged or felled by Helene, according to preliminary reports from the U.S. Forest Service. That’s $19m worth of timber.

Paraphrasing because I can’t source the quotation—which I am certain is from Look Homeward, Angel—anywhere but in my memory.

I realize there are at least a couple more efficient ways to write that number, but I like what I settled on for dramatic effect.