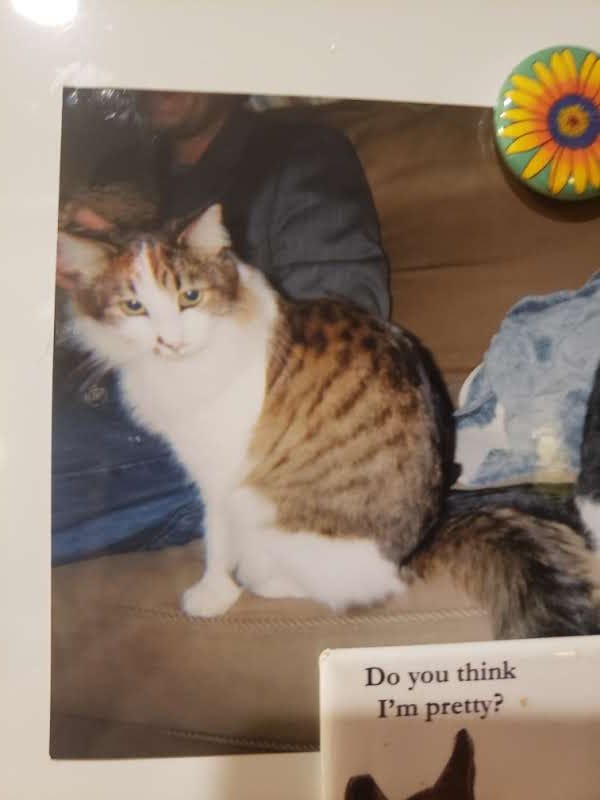

He was a good cat and he had a long life.

Remembrance of Truman, with a small supporting cast of some of his predecessors in death.

It’s taking some getting used to, this whole sleeping through the night thing. Last night I kept shifting into dim consciousness, nudged incompletely awake by pleasant dreams. In one an old friend I hadn’t seen in years, Chris, welcomed me back to an apartment we’d once shared. It differed from my memory, of course. For one thing we’d never lived together. For another it was a cell in a much larger interconnected hive, organized less like a modern apartment complex than a college dorm. I was excited to come back, particularly given my deeper understanding of the community. I lay awake for some time stewing in the mild pleasantness of the dream before remembering that Chris was dead. He’d died in 2022.

We’d met working at a coffee shop in Austin in the late-90s. Once, in ‘98 I think, he tore his MCL doing the splits to that Smashmouth song at a house party. He was just north of 300 pounds at the time and universally loved.

Chris would’ve been among the first of her peer group to find Katherine in the next, if you’re willing to entertain the idea of that kind of thing. Killed at 21 in a car accident on Cesar Chavez and South 1st in Austin in 2001, the girl I first experienced all-caps LOVE with would’ve greeted him warmly. It would’ve driven her mad being sidelined so long, so prematurely, so solitarily. Katherine had a Camaro and a supermodel pseudonym and a reputedly foolproof plan for getting rich she took with her to the crematorium. She had a high school poet’s fixation on Jim Morrison and read Ginsberg and Brautigan to me over the phone in 1995 while I, bewitched at 15, dangled cigs out the window of my bedroom in the small hours.

She said, Sit next to me.

She said, I wish there were more mystery to sex.

She said, At least now you’ve got something to throw at him, which is what her mom told her about the ring.

After that had proven prophetic and the great river of the world had gotten between us, she said, It feels like having to choose between a good husband and a soulmate.

She said, I can’t help but think I’m planning a wedding with the wrong person.

She said, I want my ring back.

I’m not sure Katherine was preceded in death even by Lacey, the old blind, deaf and off-white poodle who’d haltingly, bumpingly negotiated the many levels of her childhood home like, now that I think about it, a proto-Roomba. Were there other pets in that house? I’m not remembering any now. Kids I recall. Kim and Johnny were good procreators out there in Dripping Springs—back when it was still remote. Little brother, little sister. Then a brand new surprise sister who’d be in shouting distance of the same grade as Katherine’s own surprise baby, Maya. Kids, a llama named Jacques, musical instruments everywhere.

Don’t fall in love with a writer, her mom had warned on account of she’d fallen for a musician and look how that ended up.

He was stoned at the funeral and comforted me while I wept.

Anyway I don’t remember any cats, though there must have been. Background cats I suppose is what Dr Beth would’ve called them.

Two concepts I’ve long wished German words existed for: one’s relationship to another person’s art; one’s relationship to another person’s pets. Art is so consistent, so fixed, so frequently hanging in bathrooms where for brief but regular intervals you have nothing else to do. People often keep their bathrooms intact even as they move across town and state and country. My sister I remember always put the same fish piece in hers even as she hopscotched from Austin to Olympia to Austin to Madison to Austin to New York to San Francisco and back to Austin again. Everywhere I visited her this fish piece found me again in the bathroom. You don’t necessarily think of these things when you’re not right in front of them, but then they bop you on the nose after some random interval of geography and time and you say: Ah yes, this.

Ditto other people’s pets. It’s easy to visit a far-flung friend, have an experience of unusual tenderness and bonding with one of their pets and be startled years on to return and find the pet still ticking, still largely unchanged. Speaking I think not only for myself, pets often exist in a state of diplomatic limbo. A fairly recent entry in a Harper’s Index spoke to this: surveyed about the size of their immediate families, some shockingly high percentage of Americans revised their answers up when prompted to consider their pets. A. and I did it also: There’s two of us, we said. (But pets?) We meant four!

That was our number those months ago, driving I think to see A.’s sister and her family south of Charlotte. A family of four humans that’d been oscillating between five and seven total members for several years. A family that’s reliably kept two of the same pieces of art in their bathrooms across a pair of states and a handful of addresses—tokens of consistency that have become more numinous each time I’ve seen them. To look is to contribute a layer to an impasto of meaning to everything you see. To look is to paint the world with your sight.

We’d have to say three, now.

I can’t really make much of a list of things Truman did, not like I can for Chris or Katherine or Tyler. He didn’t do all that much, taken pound for pound. Once, he freed himself with a wild, Herculean effort from a shoddily-duct-taped cat carrier and darted across a crowded hotel parking lot in Pennsylvania at night. That’s when A. and I were newlyweds moving to Long Island for my grad school. Heart in my throat, I gave chase.

Once, when we were engaged, a few days after it’d snowed, when Truman was yet an indoor-outdoor cat, we took a long walk around our neighborhood in North Asheville and he enchanted us by tagging faithfully along the entire way.

Once, when we were first living together, before she broke my heart, before we got back together again, when I was experimenting to see if he’d follow by moving from chair to chair to bed, etc., he did, casually but unfailingly, each time.

Once, when she’d first come over to my house, Truman leapt up onto her and went directly to sleep.

Once, when I lived in a different house and had a different girlfriend, we bathed him in the kitchen sink, making him miserable and me transfixed with shame over the apparition of myriad, searching fleas.

Once, I picked him from a rowdily writhing furscape of playful sibs rollicking in the back yard of some family friends of my then-girlfriend, and when I drove him home into my life he stretched improbably tall to paw at the passenger window and let loose a howl of otherworldly pain entirely deeper and more grating and sorrowful than any such tiny body should ever have cause to produce.

Our pets change us by imposing a duty of care. I grew around Truman for 19 years, going from penniless and spendthrift unattached college kid to middle-class homeowning married employer with retirement accounts. I probably never seemed to age to Truman, so unaligned are our gerontological clocks. Even as he careered around the bends of his course, I loomed treelike at the center, the food-bringer and layer-on-of-hands, the giant god insensible to the world for decadent and unreasonable spans every night. But I failed him a lot.

I failed him with those fleas. I failed him by stingily neglecting his dental health. I failed him by letting an ear irritation blossom into a hematoma we couldn’t afford to correct. The most poignant of my failures, and the cause of the most lacerating shame, is the anger I felt toward him when he started in with the nighttime anxiety attacks. This was several years ago. He’d claw grooves in the wall around our power outlets, knock everything off of everything else, tear up any paper he could get his fangs on. He’d tear up books. And nothing I did gave him solace. He didn’t seem to want anything. He’d wake me and hide from me, under the bed, squirting away from my reaching hands. I’d finally collect him and put him upstairs in our gym. It got so that we were keeping extra food and water and a litter box up there, so frequent were his panic attacks. I learned to squash a bath towel under the door to keep him from curling his paw underneath and banging it over and over again within its frame.

Most of those bad nights I took care to respond with patience and love. I practiced intentional saintliness. I’d hold him carefully in my arms going upstairs, nuzzling his furry head and whispering to him. But not all of them—not every single time. I developed a flickering, electric phobia that his neurotic episodes were shortening my life by wrecking my sleep. Every now and then I’d fail to quell my inner sinner. I’d tug him tail-first into my grip and chuck him into the gym with something less than tenderness.

He needed medicating, of course, and finally got it, and the nights calmed. We kept pillows leaned against the outlets all the same. Took to drinking our water from screw-top bottles. Left newspapers, magazines and books out at our peril. His liver. His kidneys. Mountainous piles of wasted Fancy Feast he could only eat owing to his teeth but wouldn’t often owing to his particularity. From a peak of approximately 16 pounds he harrowed away down to, at last weighing, 6.58. You wouldn’t hear him or feel him hop onto the bed and barely registered him walking over your body.

He entered a phase we called his “head cat” phase because he slept all night next to my head. He’d pace purposively across us when hungry and I’d feed him and go back to sleep lamenting his absence and would wake up and find him there again, having been back who could say how long.

Never again.

I started breaking down at work on the 4th of July. It’d become clear that there was no longer any sense in delaying the call. He’d gone off a cliff in his upkeep over the previous several days: barely eating, constantly under the bed, sleeping all day, having a hard time getting comfortable, movements belabored and unsteady, then not eating at all, then barely drinking. We’d been keeping the door to the litter room open (the pet door in it was finally too much for him) but one night had left it merely ajar and in the morning while I wrote at my computer I heard a peeing sound from the end of the hall behind me and turned to look and saw that he’d stuck his head through the door and was staring at the litter box, peeing on the rug.

He was beyond frail. He was dying.

Of course they were closed the 4th. I left a message asking for them to call back with a recommendation for at-home euthanasia, then went home and dug a grave for my cat. The call didn’t come on the 5th so I called a service some friends had told us about on the 6th at about 9 AM. They had an open appointment at 11. We cleaned the house, weeping. I took Truman outside at 10 to give him one final taste of the world and we followed him around the yard, loosely policing. We remarked on what a peculiar walk it would seem if you couldn’t see the cat: two people aimlessly and randomly stopping and starting in small increments, tearful, staring at something on the ground.

Finally he collapsed on the coolness of the earth under our porch and he and I sat there a long time. I felt his heart fluttering and his breath fluctuating through his coat. I reflected on how lovely the birdcall was and realized it was only for me, Truman having been deaf for some time. I remembered when we’d come home from Hawaii the previous year after a 10 or 11 day trip—the longest we’d ever been separated. How I looked all over the house and finally found him asleep on the window seat of our snuggery. I sat next to him and put my hand on his head and he emitted a stunned bark of a meow and kind of fell over, so happy was he to see me.

He got up and started exploring again. There were ants out there to watch, tall grasses to nibble. He seemed many times to stop and try to (in the family parlance) “put one down,” but he had nothing to leave. At length he made his way all around the house back to the side door, obliviously passing the fresh hole. A car slowed to a halt in the alleyway behind us and A. peeled off to show Dr Beth where to park. I opened the side door on the off chance and indeed he’d seen enough and wanted back in. He made his way to the special hydration station we’d fashioned for him under the towel shelf in the master bathroom and lapped up literally the longest drink of water I’ve ever seen a cat drink, then made his way (Truman did not “walk” or “shuffle” or “amble” in his infirmity, he just barely “made his way”) out to the center of the house where Dr Beth was waiting. He evinced an interest in relieving himself so I placed him in the clean litter. Once he’d finished he made his way directly to his little plush cat bed in our studio and curled himself into it. That’s where his life would end.

We convened around him, Dr Beth with her bag of tools and Arielle and I with our box of tissue and Rudy with his curiosity and sweetness and sniffing nose. At one point, while we waited for the first of the drugs to kick in, he climbed, fat and ungainly, onto Dr Beth’s lap. She looked at us with wide-eyed delight.

That’s Rudy, we said.

He is not a background cat, she said.

Truman took one more heartbreaking stab at it, efforting from his bed onto the hardwood, but the drug was thick in him and his fluffy paws skittered under his failing legs and he wheeled back onto the plush to wait.

After she’d tested him for pain she made us a paw print and shaved two inches of fur from his shin and inserted the catheter. We stroked him and blew our noses. Rudy looked on with calm alertness. I saw Truman’s last exhale. Dr Beth listened for his heart and said,

He’s at peace.

I said, He’s gone?

And she said, He’s gone.

And I put my head down on him for the last time.

Reading this seems very familiar. When Garth's life ended we were broken and lonely for a while. I don't think I was as sympathetic as I should have been when we have talked since Truman passed. I love you all and know you will move on as much as we all do.

P.S. Did cry a little

Excellent capture of the relationship and the animal and the emotion… so poignant.